What the Champlain Condo Collapse Can Teach Us

And how we might prevent the next one

“Castles made of sand fall into the sea eventually” - Jimi Hendrix

This is the dark, grainy image I can’t seem to get out of my head. It depicts the long, skinny outstretched arm of Jonah Handler draped over the shoulder of a a fire rescue worker. Jonah is the 15 year old, Champlain South Tower resident and high school baseball player who was buried underneath concrete and rebar from his own apartment building. Bystanders heard him screaming, “Don’t leave me, don’t leave me.” They alerted rescuers who pulled him out, astonishingly, with no serious injuries.

Like the biblical parable of the reluctant Hebrew prophet Jonah, who emerged alive from the belly of the large fish on the shores of Nineveh, Jonah Handler was pulled from the bowels of his own building on the shores of Miami. His mother, Stacey Fang, tragically did not survive and became the first known casualty of the Champlain disaster. How Jonah Handler survived and emerged unscathed after a ten story drop from a building that pancaked into itself is probably the closest thing I’ve seen to a miracle in my lifetime.

97 other people, tragically, were not so lucky, when the beach-facing half of the Champlain South Building on 88th and Collins in Surfside collapsed at 1:30am on June 25th, 2021. Many of its inhabitants, I imagine, were sleeping just before their building entombed them under 13 floors of concrete. Investigators are still putting the puzzle pieces together to figure out how and why this horrific calamity happened.

Dying in your home, in your bed, under your covers, in your sleep because your building collapsed is not the way anyone should die in the wealthiest country on Earth. In an era where Covid-19 has ravished so many communities across the world, it is as unjust as it gets. It was also an unimaginable fate. With a thunderous crash, that changed. A new fear, a new nightmare, penetrated our collective psyches. For those of us who call Miami home, this incident became an overnight trauma. For those who had friends or had loved ones that perished that night, it is hard to conceive of a more unfair ending.

Death from building collapse is extremely rare, but there are places in the world where it is more common. Very little publicly available data exists on the subject. I found an incomplete list of building collapses in the world on Wikipedia, which includes those buildings who collapsed due to an extreme weather event or act of war.

I remember while reporting in Egypt I was told that I shouldn’t trust old apartment buildings or elevators. It turns out this was no urban legend. A day after the Champlain fell, a building collapsed in the coastal city of Alexandria, Egypt, that killed 5 women and injuring a 70 year old woman. Just a couple months earlier, on March 27th, a nine-story residential building collapsed in Cairo, killing 25 people. Somehow, a 6 month old baby survived. Building collapses are common enough in Egypt that someone built the website, Egyptianbuildingcollapses.org, which has sourced data on 392 building collapses since 2012, resulting in 824 homeless families, 379 injured people, and 192 deaths. All are attributed to either bad planning or poor government regulation, or both.

Clearly there is a common set of variables which have led to a pattern of dangerous building collapses in Egypt. The question I’m grappling with is whether a similar set of variables are also at play in Miami. In one singular event, Miami-Dade (population 2.7m) already has nearly half the number of deaths from building collapses as Egypt (population = 100m) had in a decade.

Now that the bodies have been recovered, the important question is: How do we prevent the next one? We hope to learn more as the forensic engineers complete their investigation, which may take months. But we can learn sooner from the glaring human errors on the part of the Condo association and Town of Surfside that needlessly endangered the lives of residents, regardless of whether these missteps were the main contributing factor that led to the collapse. We should also immediately delve into the existing systems and incentives for keeping buildings structurally safe in Miami, which appear to be as rotten as the bowels of so many of our buildings.

Some people assume that the Champlain collapse was a “black swan” event that will likely not reoccur in our lifetimes. This is a dangerous, flawed assumption. In order for the Champlain collapse to be a true anomaly, there must have been something extraordinary about this particular building. Thus far into the investigation, there is scant evidence to support this belief.

There certainly may have been a special factor or factors that contributed to the demise of the Champlain. Perhaps it was the gradual sinking of the building due to land subsidence, the construction happening next door at 87 Park, a potential construction flaw, or the deferred maintenance of the building? It could be that a “perfect storm” of multiple factors led to this catastrophe.

What is significant and troublesome for Miami building dwellers is that none of these known potential factors are unique to the Champlain South. There are sinkholes underneath other Miami buildings. There is construction happening all over Miami. There are many poorly constructed and neglected buildings all over Miami.

This incorrect assumption flies in the face of Miami’s history of building collapses. It also ignores the mounting evidence coming to light about so many other buildings in South Florida whose structural integrity is currently deemed questionable by professional engineers. Just 22 days after the Champlain catastrophe, an apartment building’s roof partially collapsed in Miami Dade county. Fortunately, nobody was killed. Miami-Dade’s own courthouse was shut down for safety concerns after inspectors found structural issues on several floors. There were 3 other condo buildings evacuated in Miami Dade County since the Champlain fell. There were another 14 buildings on the docket of the Miami-Dade Unsafe Structures Board meeting in July. The Miami Herald reported that there was a backlog of more than 1,000 unsafe structure cases in Miami Dade that had still not evaluated at the time of the Champlain’s collapse.

The reality is that the Champlain South was the weakest link in a long chain of corroded, potentially dangerous buildings in Miami Dade.

Since the collapse of the Champlain one month ago, I’ve spoken to dozens of residents, condo board members, engineers, and city officials in Surfside, Bal Harbour, and Miami Beach who provide some of the background information I used in writing this piece. Some sources and information must remain anonymous. My goal in writing this is not to point fingers but rather frame the debate we need to have as a society to better protect human lives. I may be prescriptive at times about solutions, but they are not necessarily correct and are certainly no panacea. My main message here is that it’s not enough to say “Never Again.” In order to truly honor the memories of those whose lives were lost, protect the lives of millions of people, we need to ask the right questions, hold negligent parties accountable, and make swift changes.

THE CHAMPLAIN SOUTH

As a starting point, let’s dive in to what we know about the Champlain South.

The Champlain South Tower was developed in 1981 by Nathan Reiber, Canadian lawyer who fled to Florida after he was charged for tax evasion from his coin-operated laundry business. According to several sources, Reiber paid off Surfside government officials in exchange for code exemptions, like building a 12th floor which was above the building height restriction at the time. The engineering firm hired to inspect and certify the Champlain South was Breiterman, Jurado & Associates, the same firm who certified a Coral Gables parking garage that “leaked” and “developed cracks due to a dangerous construction flaw.” In 2001, a tenant sued the Champlain South condo association over water damage in her unit, which she alleged was coming in through a cracked outside wall. In 2015, another resident sued the association for leaks coming through her “lanai unit” on the pool level of the building. The association settled with the tenant in 2018.

In October of that year, an engineering consultant named Frank Morabito, inspected the Champlain South building and produced a report on the state of the building. He documented “major structural damage” to the concrete slab below the pool deck and “abundant” cracking and crumbling of the columns, beams and walls under the building. This is what is known as concrete spalling, or “concrete cancer,” which is an erosion of concrete and rebar that is prevalent in seaside construction. Morabito wrote that “most of the concrete deterioration needs to be repaired in a timely fashion.”

This report was delivered to the board of the Champlain South Condo Association on October 8, 2018. A month later, on November 13, 2018, they submitted the report to the Town of Surfside. Two days after that, on November 15, 2018, the Champlain board met. They invited a guest speaker to the meeting, a man by the name of Ross Prieto, Building Official of the Town of Surfside.

What we know about this board meeting based on the publicly released minutes can be described at best, as a stunning level of incompetence. At worst, it amounts to a shocking cover up. The board stated that Morabito’s report had been reviewed by Mr. Prieto who according to the minutes, “determined the necessary data was collected and it appears the building is in very good shape.”

Very good shape, huh?

The board then went on to approve their 2019 annual budget of $1,329,431.00. This figure was way short of the estimated $9m needed to fix the structural problems in the building. It is not clear how these funds were allocated.

It is not clear if any of the residents of the Champlain South were made aware of the details of Morabito’s report at any point before April 2021, when the new board president Jean Wodnicki sent a letter to residents referencing it and warning residents that “concrete deterioration is accelerating.” Wodnicki actually seems like a highly effective board member. She was transparent about the 2018 report, the current state of the building, and the plan to remedy the structural problems. The next challenge for the Champlain Towers was how to pay for these necessary repairs, which had ballooned from $9m in 2018 to more than $16m in 2021. The building had only $707,003 in cash on hand. They were looking into financing at the time of the collapse.

Unfortunately, it was too little, too late.

Why did the Condo association board bury the 2018 Morabito report? Did they misread the engineering report or did they just not want to foot the bill ?

Why did the Town of Surfside assist in this burial ?

As the lawsuits fly in, these answers may become apparent.

NONSENSICAL, IMAGINARY REGULATIONS

Miami-Dade County Section 8-11 (f) is a county statute that "requires buildings at age 40 with 11 or more tenants to be inspected structurally for the first time, and then it requires recertification every 10 years after that. What typically happens is that buildings get notified by the county at some point AFTER their 40th anniversary, and then they technically have 90 days for a professional engineer to certify in writing that the building is structurally and electrically safe. Then, if something is found to be unsafe, they have to fix it within 150 days.

The truth is that nothing about this code is actually grounded in reality. It’s a make-believe law with make-believe timelines. Sources in several municipalities have told me that a “shockingly high percentage” of buildings over 40 in Miami Dade County still have not been re-certified. This happens for several reasons. Buildings typically wait for their notice to begin the process of inspecting their buildings. Sometimes the county sends out the notices late. 90 days is a reasonable window to get the written assessment back, but if the building is in bad shape, which is the case for so many Miami-Dade buildings, it is impossible to raise the money, get the permits, and then bring the buildings up to code with a “full remediation” within 150 days. So what ends up happening is that buildings drag their feet well beyond 40 years, exposing their residents to potential risk along the way. It is a logical first step that political leaders like Mayor Daniela Cava Levine of Miami-Dade are auditing the re-certification process for buildings 40 and over to make sure the buildings are compliant and safe. But this is just the county doing its actual, damn job. It’s a shame that it took nearly 100 dead for the city and county to think code compliance around building safety mattered.

Americans typically get to see a doctor for check ups every year. Buildings inspect elevators every year. Why do our buildings only get inspected for “concrete cancer” and other life threatening ailments every 40 years ?

40 years is a great amount of time for the aging of a fine wine or for the ancient Hebrews to wander the Sinai desert. I’m no engineer, but 40 years strikes me as an absurdly long amount of time for a building on the beach to get its first inspection. I’m not sure what the new limit should be, but if we’re optimizing for saving human lives rather than property values, it should be a very conservative number. 10 years feels much more appropriate than 40 years. Imagine if the Champlain was required to be inspected and fully re-certified in 1991, 2001, and 2011. Would it still have collapsed in 2021?

I posed this question in an interview with an actual civil engineer. Ben Messerschmidt, P.E., is a native South Floridian who operates Epic Forensics and Engineering, which specializes in the structural certifications of buildings in Florida. He told me,

“Buildings don’t have voices but they like to tell you what’s going on. Cracks can be innocent, or more telling that there is a structural loss.”

If buildings cracks can tell you about the health of a building, shouldn’t we examine them more often? Bear in mind that the cost of the inspection of the Champlain South would have cost less than $20,000 in today’s market. In 1991, it would have cost significantly less. There’s no good financial reason for these buildings to wait 40 years to get their first inspection. Paying the hefty repair bills that could follow such an inspection is another story. It seems like that is the reason the condo associations defer the inspections. Knowing the truth means that money will have to go out of pockets. So the idea is to kick the can as far down the road as possible.

Furthermore and most alarmingly, the 40- year recertification statute does nothing to ensure the safety of those living in older buildings that were constructed prior to the strengthening of the building codes in 1992 after Hurricane Andrew, that are not yet 40. In other words, buildings aged 30-39, essentially any building constructed during Miami’s drug fueled construction boom, are probably in the highest risk category right now because they may have been built using the same standards as the Champlain and may never have had any meaningful inspections. They need to be inspected and re-certified for safety immediately. The Champlain, built in 1981, had known “major structural damage” at the age of 37. It was technically still compliant with the 40 year code when it crumbled before its 41st birthday. That fact alone should be the nail in the coffin for this ridiculous, rotten statute.

CORRUPTION

The challenge is that even if we emerge with a more reasonable statute, we need to appoint officials that enforce it. Laws are only as good as the politicians and city officials are incorruptible. In the Banana Republic of Miami, corrupt and government go together like rice and beans.

This is particularly true in the construction industry, where bribery and kickbacks are the norm. The former top building official in Miami Beach, Mariano Fernandez was sentenced to two years of house arrest after striking a plea deal for accepting handouts from hoteliers. Fernandez was not the exception. He was the rule. Andres Villareal, another building official from Miami Beach went to prison for 18 months after pleading guilt to two counts of unlawful compensation. He was one of 3 separate Miami Beach building officials admitted to accepting bribes in exchange for permits in a 3 year period.

The construction company Munilla Construction Management, or MCM, has received nearly $150 million in government contracts since 2011, despite the fact that former Miami mayor, Carlos Gimenez, who oversaw many of those contracts, has two sons who have worked for the firm, and his wife Lourdes is a cousin of the owners, the Munilla brothers. MCM contributed to Gimenez’s campaigns and then his son worked to lobby his government for contracts, which were often (surprise) won by MCM. This overt and shameless racket resulted in an ethics commission which was effectively a slap on the wrist for Gimenez who is now a Republican representative of Florida’s 26th district in the House. MCM was also the firm who oversaw the construction of the pedestrian bridge at FIU that collapsed and killed 6 people. The firm was fined for its role in the collapse, filed for bankruptcy protection, yet (surprise, again), emerged from the ashes to win more lucrative government contracts, including a Miami International Airport job worth $70m.

The construction of the top floors of the Champlain South and North that were built in violation of code, yet somehow became legal, is par for the course in Miami.

Remember, Ross Prieto, the building official who certified the Champlain South to be “in very good shape” ? He worked in Miami Beach for a stint, and has bounced around to many different Miami municipalities. In 1997, he was the assistant director of building and zoning in Miami Shores when the Biscayne Kennel Club prematurely collapsed on workers during a demolition project, killing two brothers.

Somehow, he also kept getting jobs. See the pattern here?

Most recently, Prieto worked as a private contractor for C.A.P. Government, a private firm that appointed him the building official in Doral, where he is currently taking a leave of absence. Did you read that carefully ? It turns out the government doesn’t even do its own inspections in Miami. They outsource it to private firms, who then hire contractors like Prieto and pay them $77.50/hour, according to public records, to inspect our buildings for safety. This means that the public interest of safety is being outsourced to private firms whose main agenda is profit. It’s easy to see how this can lead to conflicts of interest.

Should our safety be outsourced to incompetent contractors that seem to never be held accountable for failing? Should building officials who serve the public be hired guns from private for-profit firms? If municipalities can’t afford to hire a qualified inspector for $77/hour to protect their residents, it seems like there may be a bigger problem here.

If government cannot be trusted to keep condo residents safe, who can be?

CONDO ASSOCIATION (MIS)MANAGEMENT

Half of all Floridians, nearly 11 million people, live in in a condo. There are nearly 50,000 registered condo or homeowners associations in the state that was largely built by strip mall and condo developers. We need to better protect residents from incompetent, negligent, or dangerously frugal condominium associations.

Condos are also not what they used to be. I remember as a teenager, one of my first summer hustles was trying to do maintenance work for people who were out of town most of the year. I printed thousands of flyers and put them up on condos between Xmas and New Years trying to get customers. I got one phone call from those thousand flyers. The person told me they don’t need my services. Any problems they have they will deal with when they get back to the condo next December.

This is how it was. Florida condos were nearly completely empty in summer. Suddenly around Thanksgiving you start to see the Quebec, Ontario, and New York license plates and you know that the “snowbirds” are in town. This means lots of traffic, lobster-pink sunburns, and no early reservations left at most restaurants. “Snowbirds” are typically wealthy individuals who often spend just a few weeks per year in their unit, which is their 2nd, 3rd, or 4th home.

What’s changed is that there are native Floridian and Latin American birds co-mingling with the “snowbirds” in condos now. Partially due to the housing crunch in South Florida, which has led to astronomically high prices for single family homes in Miami, you see more and more young families choosing to buy condos and live in them year round. But many Florida condos are still controlled by the legacy owners who only live in Florida a few weeks a year. These are often the people making decisions that affect the lives of people who live in the condo year round. The problem is that “Snowbirds”, who view the condo more as an investment than a home, do not share the same incentives as people who sleep in their unit every night of the year. If you view a condo as an investment property your decision-making framework will be financially motivated, and will not be as focused on quality of life or safety considerations. Decision makers who are not on site are also less likely to understand the day to day problems occurring in the building.

I met up with a couple residents of a Bal Harbour condo, both middle aged dads with wives and young children living year round in a building just about a mile up the street from the Champlain South. 6 days after the Champlain fell, no engineer had come by to inspect their building, and they had some concerns about disrepair in their garage. They had at that point no information about the safety of their structure from the city, or our own association. So they invited me to see the garage. They don’t wish to reveal the name of the building since, in his words of one of them, “I don’t like to shit where I eat.” The other resident said, “It will kill the property values if this goes public.”

What we saw in the garage shocked us. There is widespread concrete corrosion, exposed rebar, giant cracks, leaks, flooded areas, damp spots in concrete, mysterious condensation in concrete, and rusted pipes throughout. Some of the worst areas were right underneath the pool deck, the place believed to be the first point of failure at the Champlain.

Bear in mind that this condo, like many buildings in the area, has a mandatory valet service. Residents are not allowed to park their own cars, which means they never actually get to see their own underground garages. Some of the most vital structural components of these massive buildings are hidden from plain sight. It is likely that most residents had no idea that this is the state of their own building.

According to numerous building employees I spoke with, including the property manager, these issues have been prevalent for years. It is not clear if anyone on the board was aware of the issues. The president and vice-president of the board both live in Canada and as of July 21, 2021, had not stepped foot in the building in at least 18 months. As this resident said to me,

"These guys are managing this building from thousands of miles away. How can they be responsible for the safety of my children when they don’t even sleep in the building?”

Absentee board members, with different incentives, running their condos from a distance, certainly seems like recipe for mismanagement and negligence. To ensure better outcomes for these buildings, perhaps government should require condominium owners to reside at least 6 months per year in the condominium in order to serve as a director in a condo association.

We also need to drastically improve the transparency for residents about the state of their buildings and all inspection reports that pertain to safety. The law should require structural, mechanical, and electrical inspection reports be publicly available data, regardless of whether they are submitted to the city. That will protect residents, owners, tenants, and potential buyers from living in or purchasing condos in derelict buildings. It will also prevent the obfuscation of relevant information from residents to save money on needed maintenance or to artificially prop up the value of their properties, at the expense of new buyers or renters. Disclosure of information about human safety should be available to all.

Finally, we should be questioning whether we should put complex, life or death engineering decisions in the hands of volunteer condo boards with no requisite background in engineering and, often no willingness or ability to shell out money. Should volunteer boards with financial motives and no engineering experience be responsible for overseeing engineering plans that pertain to public safety ?

Perhaps cities should consider requiring an oversight committee of certified engineers with no financial interests in these buildings to advise them on making engineering hires and analyze engineering reports professionally.

Some additional protections for residents could be provided by the private sector. Insurance companies are already demanding tougher inspections, and hopefully this will also lead to inspections that come before the fifth decade of a building’s life. It would be great to see a real estate marketplace app that not only lists condos for sale, but also provides historical inspection reports and independent, verified reviews of the associations by owners. That way a potential buyer or tenant can see for themselves how trustworthy and competent an association is before they put their lives in their hands. (Yes, this was a free business idea for all the recent arrivals to Miami’s start up scene, or maybe just a new feature on Zillow).

The honeymoon for associations and corrupt government officials operating in cahoots with one another, producing fictitious board meeting minutes that hide the dangerous reality from residents, must end now.

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS

In its listing on Condos.com, the Champlain South Tower was described as “an idyllic location directly on the pristine beach, with a gorgeous vista of the Atlantic Ocean”. The marketing language boasts “light-filled open floor plans”, “over-sized balconies,” and a “luxury high-rise lifestyle”. It mentions the shared perks like a swimming pool, a fitness center, a spa, a sauna, a business center, and of course, access to a private beach. It is sold the same way Miami Beach has always been sold. A private paradise. An escape. A warm place in the sun.

But owning a slice of paradise on the barrier island of Miami Beach comes with costs and risks that don’t make it into the ad copy. A building may be in violation of code, structurally unsafe, or have special assessments due that make the actual price much larger than you see on Condos.com. Shared fiduciary responsibilities are swept under the rug or perpetually deferred.

What is happened in the Champlain appears to be a tragedy of the commons. This is the root problem underlying many of the greatest conflicts facing humanity, including the environmental crisis. The definition, according to Wikipedia, is as follows: “If there is a common area, individual users, who have open access to a resource unhampered by shared social structures or formal rules that govern access and use, will act independently according to their own self-interest and, contrary to the common good of all users, cause depletion of the resource through their uncoordinated action.” It is the moral lesson at the heart of the prescient Dr. Seuss book, The Lorax. Individuals or nation states tend to act in their own self interests, at the expense of the greater good, until there is no greater good left.

The tragedy of the commons is the reason that our shared seas are overfished and our shared lands are overdeveloped. It is also the primary reason condos fall into disrepair and neglect. Everyone wants to receive the public benefits of their condo life, the beautiful shared views and amenities like the pool, spa, and beach. But nobody wants to personally foot the bill themselves. The dreaded “special assessments,” the additional charges to pay for repairs or renovations of the condos, compile as nobody wants to pay for things that benefit everybody. It’s a perplexing aspect of human nature, much more akin to our primate cousins than an intelligent, rational creature that prioritizes long term survival. But it is hard to deny that this part of the way humans are wired. Given that humans will take, take, take until there is nothing left, shouldn’t we protect ourselves from our own nature? Shouldn’t there be a stricter set of laws governing these associations that so often repeat this dangerous behavior pattern?

We know that once the truth about the repair costs came to light at the Champlain South, residents could not all agree to pay $80-$200K in fees per unit owner.

Shouldn’t condos be required to maintain reserves ? Perhaps the amount can be commensurate with the age of the building, or the time that has lapsed since an inspection, with a larger factor if the building is on the beach ? Alternatively, there could be a statute requiring any structural or safety related “special assessments” be automatically prioritized and paid for in a timely fashion (less than 3 months?). If not, entire buildings should be condemned. Work it out, or everybody loses. Some, hopefully non-corrupt government body can step in to seize the assets of any bad apples who refuse to pay for required maintenance. Banks and financial services companies can of course get in on the action to finance “special assessments” for those who cannot afford them. Opportunity can come out of this crisis.

THE REAL PRICE TAG OF LIVING WITH MOTHER NATURE

The silent, unnamed accomplice of the Champlain tragedy is Mother Nature herself. For a building to exist in Miami Beach it must commit to a long term, war of attrition against a truly formidable foe, Mother Nature. She is fierce, relentless, and has many different weapons in her arsenal. Salty air, rain, wind, and seawater corrode ultimately consume everything in their path. Every single day that you don’t maintain your structure is another day you are losing in this war.

“You’re getting blasted with chlorides from the salt laden air every single day. Anything that’s rubber will start to get more brittle sooner. Concrete is porous, so you’re going to get the chlorides interacting with that embedded steel sooner rather than later, which leads to cracks and steel expansion and spalling,” Ben Messerschmidt, P.E. told me in an interview.

Messerschmidt is a structural and forensic engineer who regularly inspects these buildings by the beach, recommends a more regular maintenance regimen for coastal buildings.

“I consider these properties on the Beach to be, essentially, marinas with condos on top of it. In a marine environment, as cracks widen, the amount of water that gets in increases. Remember that over time, water carves through mountains. In this environment, structural loss grows exponentially if nothing is done.”

People often assume Miami Beach, including Surfside and Bal Harbour, is a contiguous part of Miami, but if you look at it from above you see that it is not geographically connected to the continental U.S. It is a barrier island designed by nature to absorb large volumes of sea water from tidal surges, in order protect the mainland, the city of Miami, from storms and waves. Historically, it did so with large sand dunes, native grasses, and porous limestone rock called oolite on the eastern side. On the western side of the island, you have wetlands and swampy mangroves which are filled with sinkholes. To make way for condos and hotels, the natural design of the barrier island was decimated. Concrete and cement do not provide much protective functionality for the rest of the city. It was a questionable long term decision to develop Miami Beach in this way, but alas, Miami followed the money.

Here’s a little secret realtors will not tell you: Miami Beach is constantly, dangerously eroding. Yes, that’s right. The giant mound of sand that props up the entire barrier island is losing its own foundation. Over the years, I’ve witnessed the land disappear in certain stretches until there’s barely any beach left and the tide starts smacking into the outer walls of buildings. Eventually, the US Army Corps of Engineers get called in to dredge. In their last big project, they poured enough sand to fill 800,000 cubic yards of land where the beach used to be. According to Elizabeth Wheaton, assistant director of environment sustainability for the City of Miami Beach, “we’ll always need to re-nourish our beaches.” “Re-nourish” is a euphemism for “artificially re-construct”. In order for Miami Beach to continue to exist, it will need constant reconstructive surgery.

The bigger, related problem for Miami Beach is that the “marine environment” is only getting more marine. Flooding, the most costly weather event for Americans, costing on average $4.6 billion per year, is getting worse and more frequent in Miami Beach. Flooding can happen from rain water, high tides, and/or storms. Miami Beach has already invested $500m to retrofit pumps and build sea walls, but is far from solving the issue.

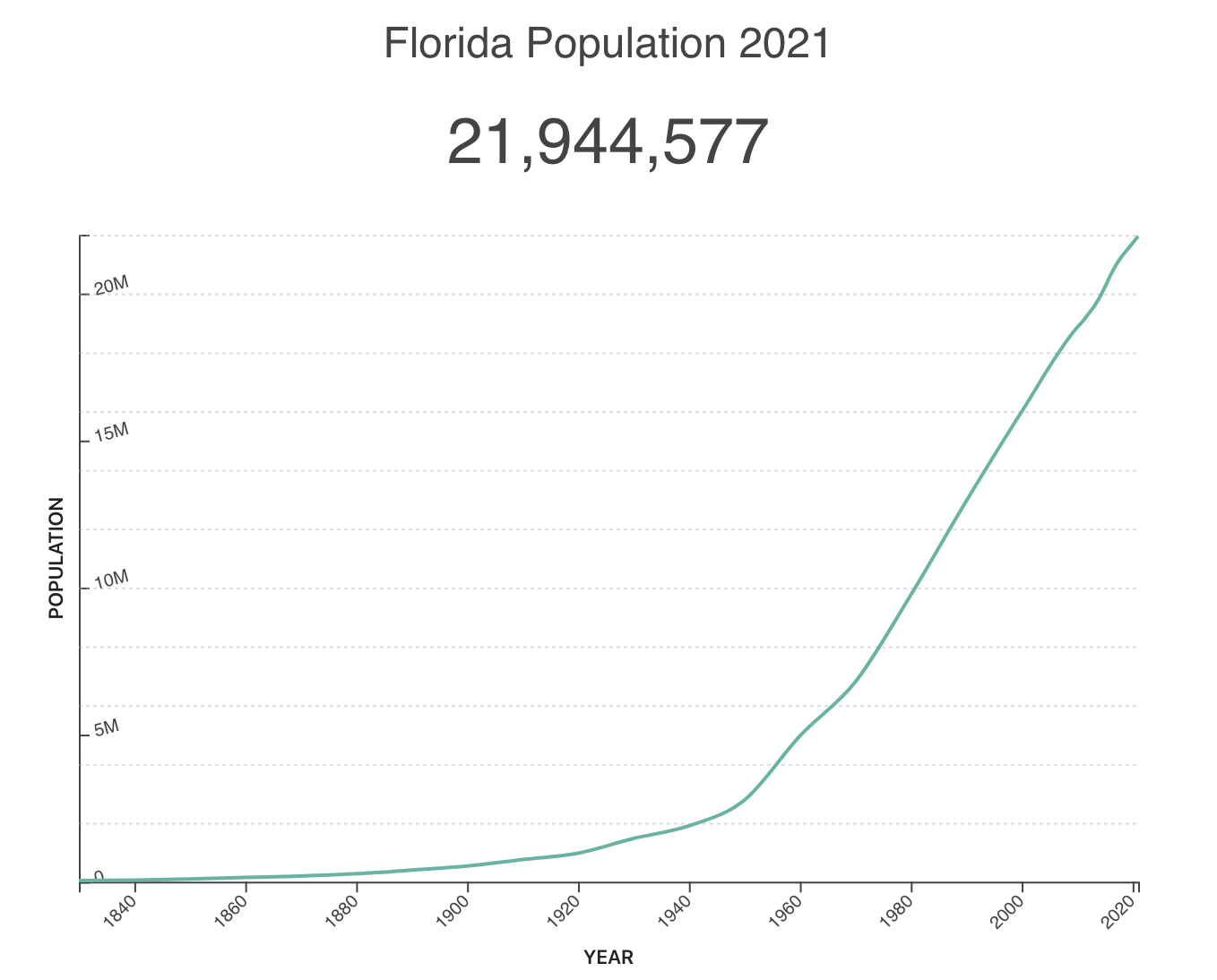

Miami, and particularly Miami Beach, is extremely vulnerable. We have more capital and infrastructure at risk from climate change than any city on Earth. With each passing day, the war against Mother Nature becomes less winnable, and more costly. Given what scientists claim will happen to the shoreline of Miami over the next twenty years, with roughly another foot of sea water swallowing the land, how much money will have to be spent to keep Miami Beach inhabitable ?

Imagine if sea levels continue to rise at the same, or greater rate. What will the price tag be to keep people living safely in Miami Beach be over the next 100 years ?

We’ve probably invested too much to quit the cash cow that is Miami Beach, but we need to understand the effects of the decision to keep investing here. Clearly, engineers will continue to profit. According to Messerschmidt, “This is the kind of stuff engineers dream about. Whether there are levees like in New Orleans or perhaps even building another barrier island, we’re going to have to engineer something to keep people here 100 years from now.”

WHO IS LOSING ?

As the Florida’s coastal population surges, developers and engineers are clearly winning. The question is, who is losing in this equation? Here’s a clue. It’s not the insurance companies.

Insurance companies are been bailing on Florida since Hurricane Irma. The Champlain catastrophe is only making them more squeamish. As Adam Lopatin, senior vice president at USI Insurance Services, told the New York Times, “It all comes down to profitability for the insurance companies. And right now, writing business in Florida is not profitable.” Unless premiums skyrocket, it will never be profitable to insure coastal Florida.

The only insurance company still writing homeowners in many parts of Florida, including Miami Beach and most of coastal Miami, is Citizens, the state insurance company supported by Florida tax payers, who step in when private companies refuse to write policies in a specific area. This “insurance company of last resort” is now the only option in much of coastal Florida. Citizens is now writing more policies in Florida than any other private carrier.

Let’s break this down in simple English: Insurance companies, which specialize in risk assessment, have looked at historic data and used it to infer future projection models, which unanimously deem it too risky to write policies in much of Florida.

Citizens is not a real, private insurance company. It is the Florida state government posing as an insurance company. This means that Florida taxpayers are the backstop in case of catastrophic events. In other words, any poor decisions made by this generation have the potential to bankrupt our own children and grandchildren. Future Florida taxpayers are effectively writing our own pseudo insurance policies now. It’s a gamble that no private companies are willing to take, but is forced on Florida tax payers. This too should be up for debate.

Why should future Florida tax payers foot the insurance bill for private developers and wealthy snowbirds to profit off of our shared resources now?

We can’t turn back the clock on the decisions made in the past, but there should be a public state-wide debate about any future development in flood zones given the rising seas, the rising costs, and the uninsurability of these buildings. It’s a financial disaster waiting to happen, with a ton of risk and no upside for average Floridians. This is how disaster capitalism works, preying on poor and middle class with no meaningful exposure for the smaller demographic of wealthy people who can afford to own properties in coastal Florida.

REDEMPTION

“Look at the castles!” my 4 year old son exclaimed, peering out the window from his car seat, as we drove up Collins Avenue. After returning back to civilization after 5 months living in an Airstream in national and state parks, he marveled at the 16, 20, 25, 30, floor condominiums that stretch for miles from South Beach all the way up to Sunny Isles, like a row of tightly packed dominos. Growing up in North Miami Beach in the 1980’s, I watched these buildings sprout up before my eyes, with names like Bellini, Acqualina, and Trump Towers, blocking the sight of one of the most beautiful coastlines in the world. My son had no idea there was even a beach behind these buildings. All he could think of were Elsa’s gigantic ice castles from the animated film, “Frozen.”

After stints in NYC and San Francisco, my family and I moved back to Miami in late 2020 and temporarily moved into a “castle” in Bal Harbour while we are renovating our house. This is my first time living in a condo. I jog past the Champlain often and we are connected to several people who either escaped from, or who perished in the building that night.

Like our whole community, we are feeling the trauma of this event. We were shocked to see a building we’ve known for years turned into a smoldering heap of rubble. Seeing the yellow emergency tape and the media scrum from all over the world in our local beach felt surreal.

Living on the 11th floor of an older building a mile away from the Champlain has certainly added a source of anxiety that we’ve never known before. We inspected our own garage and are actively pushing our association to fix any potential structural issues. It seems that progress is being made but we are still admittedly uneasy about building life. For a couple weeks, we didn’t hear our wind chimes or the ocean breezes at night. Every creak of the building or bolt of thunder jolted us out of bed. Immediately after the tragedy, all we heard were sirens; hundreds of ambulances, fire rescue, police, emergency vehicles, and eventually, President Biden’s motorcade whizzed by on Collins Avenue just below us. From our balcony at dawn we watched the fleets of dump trucks driving south empty. They drove back north at sunset, filled to the brim with debris from the Champlain. For so many nights, we prayed for miracles for the families of our neighbors who had loved ones missing. Now we pray for their comfort.

I keep thinking about Jonah Handler. How did he survive? How is he doing? What will he make of this event once he grows up ? I think about the story of his namesake, Jonah the prophet, read by Jews on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The story focuses on the city of Nineveh, which is described as a large and corrupt city. G-d asks Jonah to warn them to change their ways and save the city from his wrath. Jonah initially resists his mission, tries to escape by boat, when ultimately G-d steps in with a big storm. Jonah resists again and tries to commit suicide by jumping in the water.

“And the LORD prepared a great fish to swallow up Jonah; and Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights.” - Maftir Yonah (The Bible)

G-d eventually sends in the big guns, or in this case, a big fish to swallow Jonah and escort him to Nineveh. Inside the dark, belly of the sea creature, Jonah ultimately accepts his fate as a prophet. He is spit up on the shores of Nineveh, where he warns the people that G-d will destroy their city if they don’t change their ways in 40 days or less.

Miami, in some ways, is Nineveh. We are a large city plagued by corruption. We myopically developed land needed to protect people from Mother Nature. We greedily sold it at a price that hides the true cost. We selfishly refused to pay for our own neighbors to live safely. We optimized for short term gains over human safety.

But Miami, in some ways, is not Niniveh. We put everything on hold to find people in the rubble, calling in the best teams in the world to try and help. We rallied together as one community after this tragedy, raising millions of dollars for the survivors and families of the victims. We all knew someone who knew someone in the building that night. We honored them in large and small ways.

The question, for Miami’s future, is which version of our city will prevail. Will we be a city that prioritizes safety and the common good ? Or will we continue to allow corruption and private interests to continue to threaten us all ?

In the biblical story of Jonah, G-d says, “Should not I have pity on Nineveh, that great city, wherein are more than six score thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand?”

Miami, after the Champlain, can no longer depend on G-d’s pity.

For Jonah Handler, for the families of the men, women, or children whose lives were tragically cut short, and for the millions of people who continue to live and work and dream in Miami, we must redeem ourselves at the speed of Nineveh.